In almost all countries, if you compare the wages of men and women you find that women tend to earn less than men. These inequalities have been narrowing across the world. In particular, over the last couple of decades most high-income countries have seen sizeable reductions in the gender pay gap.

How did these reductions come about and why do substantial gaps remain?

Before we get into the details, here is a preview of the main points.

- An important part of the reduction in the gender pay gap in rich countries over the last decades is due to a historical narrowing, and often even reversal of the education gap between men and women.

- Today, education is relatively unimportant to explain the remaining gender pay gap in rich countries. In contrast, the characteristics of the jobs that women tend to do, remain important contributing factors.

- The gender pay gap is not a direct metric of discrimination. However, evidence from different contexts suggests discrimination is indeed important to understand the gender pay gap. Similarly, social norms affecting the gender distribution of labor are important determinants of wage inequality.

- On the other hand, the available evidence suggests differences in psychological attributes and non-cognitive skills are at best modest factors contributing to the gender pay gap.

Differences in human capital

Differences in earnings between men and women capture differences across many possible dimensions, including education, experience and occupation.

For example, if we consider that more educated people tend to have higher earnings, it is natural to expect that the narrowing of the pay gap across the world can be partly explained by the fact that women have been catching up with men in terms of educational attainment, in particular years of schooling.

Indeed, since differences in education partly contribute to explain differences in wages, it is common to distinguish between ‘unadjusted’ and ‘adjusted’ pay differences.

When the gender pay gap is calculated by comparing all male and female workers, irrespective of differences in worker characteristics, the result is the raw or unadjusted pay gap. In contrast to this, when the gap is calculated after accounting for underlying differences in education, experience, and other factors that matter for the pay gap, then the result is the adjusted pay gap.

The idea of the adjusted pay gap is to make comparisons within groups of workers with roughly similar jobs, tenure and education. This allows us to tease out the extent to which different factors contribute to observed inequalities.

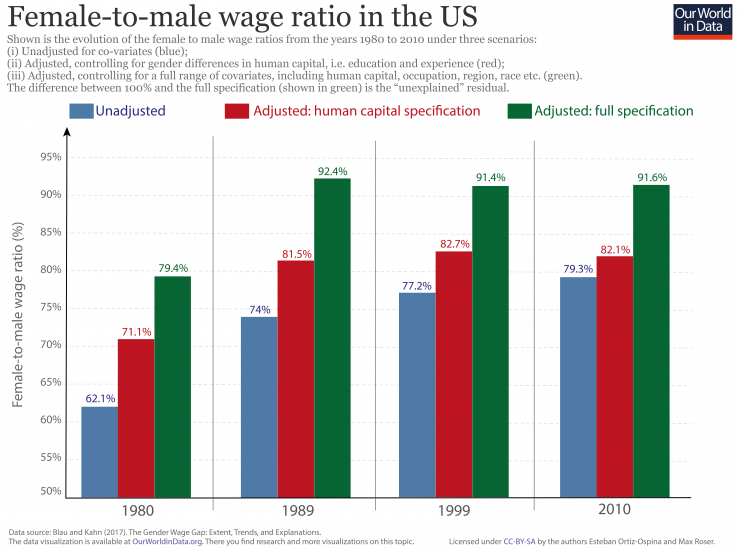

The chart here, from Blau and Kahn (2017) shows the evolution of the adjusted and unadjusted gender pay gap in the US.1

More precisely, the chart shows the evolution of female to male wage ratios in three different scenarios: (i) Unadjusted; (ii) Adjusted, controlling for gender differences in human capital, i.e. education and experience; and (iii) Adjusted, controlling for a full range of covariates, including education, experience, job industry and occupation, among others. The difference between 100% and the full specification (the green bars) is the “unexplained” residual.2

Several points stand out here.

- First, the unadjusted gender pay gap in the US shrunk over this period. This is evident from the fact that the blue bars are closer to 100% in 2010 than in 1980.

- Second, if we focus on groups of workers with roughly similar jobs, tenure and education, we also see a narrowing. The adjusted gender pay gap has shrunk.

- Third, we can see that education and experience used to help explain a very large part of the pay gap in 1980, but this changed substantially in the decades that followed. This third point follows from the fact that the difference between the blue and red bars was much larger in 1980 than in 2010.

- And fourth, the green bars grew substantially in the 1980s, but stayed fairly constant thereafter. In other words: Most of the convergence in earnings occurred during the 1980s, a decade in which the “unexplained” gap shrunk substantially.

Education and experience have become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages in the US

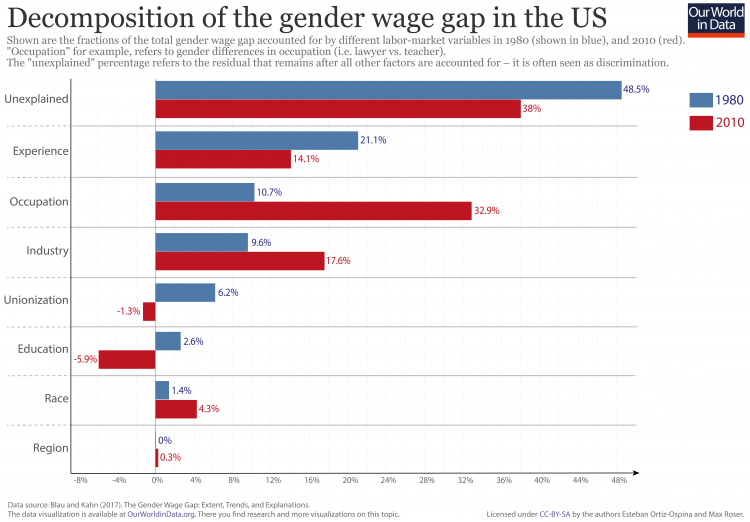

The chart here shows a breakdown of the adjusted gender pay gaps in the US, factor by factor, in 1980 and 2010.

When comparing the contributing factors in 1980 and 2010, we see that education and work experience have become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages over time, while occupation and industry have become more important.3

In this chart we can also see that the ‘unexplained’ residual has gone down. This means the observable characteristics of workers and their jobs explain wage differences better today than a couple of decades ago. At first sight, this seems like good news – it suggests that today there is less discrimination, in the sense that differences in earnings are today much more readily explained by differences in ‘productivity’ factors. But is this really the case?

The unexplained residual may include aspects of unmeasured productivity (i.e. unobservable worker characteristics that cannot be controlled for in a regression), while the “explained” factors may themselves be vehicles of discrimination.

For example, suppose that women are indeed discriminated against, and they find it hard to get hired for certain jobs simply because of their sex. This would mean that in the adjusted specification, we would see that occupation and industry are important contributing factors – but that is precisely because discrimination is embedded in occupational differences!

Hence, while the unexplained residual gives us a first-order approximation of what is going on, we need much more detailed data and analysis in order to say something definitive about the role of discrimination in observed pay differences.

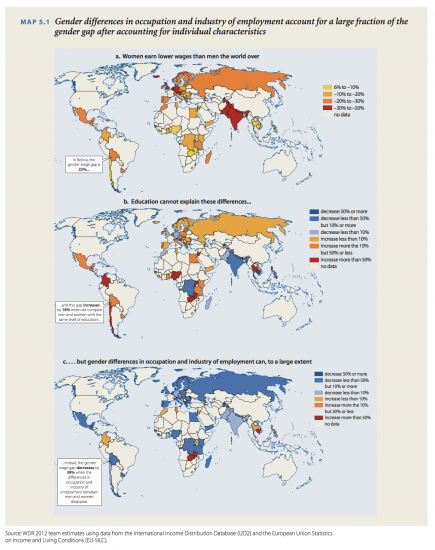

The set of three maps here, taken from the World Development Report (2012), shows that today gender pay differences are much better explained by occupation than by education. This is consistent with the point already made above using data for the US: as education expanded radically over the last few decades, human capital has become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages.

This blog post from Justin Sandefur at the Center for Global Development shows that education also fails to explain wage gaps if we include workers with zero income (i.e. if we decompose the wage gap after including people who are not employed).

Gender pay gap after adjusting for education and occupation – WDR (2012)4

Looking beyond worker characteristics

All over the world women tend to do more unpaid care work at home than men – and women tend to be overrepresented in low paying jobs where they have the flexibility required to attend to these additional responsibilities.

The most important evidence regarding this link between the gender pay gap and job flexibility is presented and discussed by Claudia Goldin in the article ‘A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter‘, where she digs deep in the data from the US.5 There are some key lessons that apply both to rich and non-rich countries.

Goldin shows that when one looks at the data on occupational choice in some detail, it becomes clear that women disproportionately seek jobs, including full-time jobs, that tend to be compatible with childrearing and other family responsibilities. In other words, women, more than men, are expected to have temporal flexibility in their jobs. Things like shifting hours of work and rearranging shifts to accommodate emergencies at home. And these are jobs with lower earnings per hour, even when the total number of hours worked is the same.

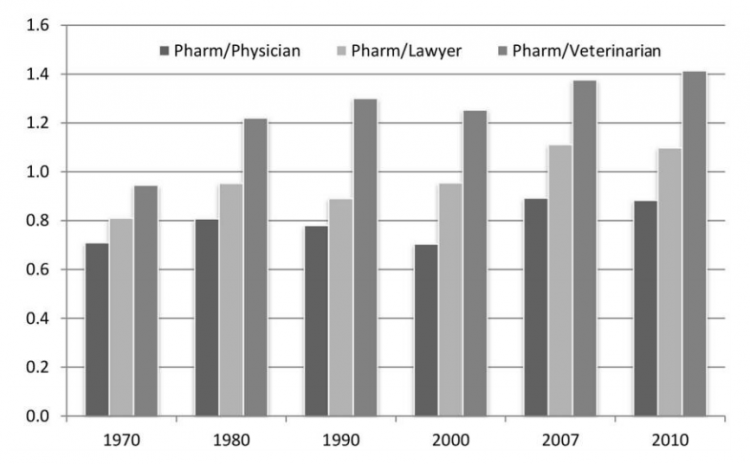

The importance of job flexibility in this context is very clearly illustrated by the fact that, over the last couple of decades, women in the US increased their participation and remuneration in only some fields. In a recent paper, Goldin and Katz (2016) show that pharmacy became a highly remunerated female-majority profession with a small gender earnings gap in the US, at the same time as pharmacies went through substantial technological changes that made flexible jobs in the field more productive (e.g. computer systems that increased the substitutability among pharmacists).6

The chart here shows how quickly female wages increased in pharmacy, relative to other professions, over the last few decades in the US.

Female median earnings of full-time, year-round pharmacists relative to other professions, 1970-2010, US – Goldin and Katz (2016)7

Closely related to job flexibility and occupational choice, is the issue of work interruptions due to motherhood. On this front there is again a great deal of evidence in support of the so-called ‘motherhood penalty’.

Lundborg, Plug and Rasmussen (2017) provide evidence from Denmark – more specifically, Danish women who sought medical help in achieving pregnancy.8

By tracking women’s fertility and employment status through detailed periodic surveys, these researchers were able to establish that women who had a successful in vitro fertilization treatment, ended up having lower earnings down the line than similar women who, by chance, were unsuccessfully treated.

Lundborg, Plug and Rasmussen summarise their findings as follows: “Our main finding is that women who are successfully treated by [in vitro fertilization] earn persistently less because of having children. We explain the decline in annual earnings by women working less when children are young and getting paid less when children are older. We explain the decline in hourly earnings, which is often referred to as the motherhood penalty, by women moving to lower-paid jobs that are closer to home.”

The fact that the motherhood penalty is indeed about ‘motherhood’ and not ‘parenthood’, is supported by further evidence.

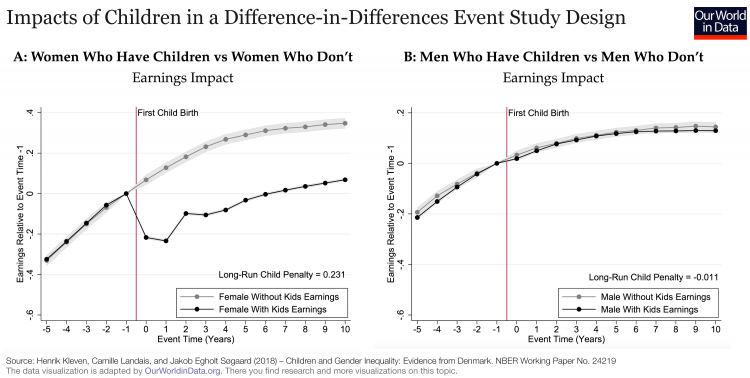

A recent study, also from Denmark, tracked men and women over the period 1980-2013, and found that after the first child, women’s earnings sharply dropped and never fully recovered. But this was not the case for men with children, nor the case for women without children.

These patterns are shown in the chart here. The first panel shows the trend in earnings for Danish women with and without children. The second panel shows the same comparison for Danish men.

Note that these two examples are from Denmark – a country that ranks high on gender equality measures and where there are legal guarantees requiring that a woman can return to the same job after taking time to give birth.

This shows that, although family-friendly policies contribute to improve female labor force participation and reduce the gender pay gap, they are only part of the solution. Even when there is generous paid leave and subsidized childcare, as long as mothers disproportionately take additional work at home after having children, inequities in pay are likely to remain.

The discussion so far has emphasised the importance of job characteristics and occupational choice in explaining the gender pay gap. This leads to obvious questions: What determines the systematic gender differences in occupational choice? What makes women seek job flexibility and take a disproportionate amount of unpaid care work?

One argument usually put forward is that, to the extent that biological differences in preferences and abilities underpin gender roles, they are the main factors explaining the gender pay gap. In their review of the evidence, Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn (2017) show that there is limited empirical support for this argument.9

To be clear, yes, there is evidence supporting the fact that men and women differ in some key attributes that may affect labor market outcomes. For example standardised tests show that there are statistical gender gaps in maths scores in some countries; and experiments show that women avoid more salary negotiations, and they often show particular predisposition to accept and receive requests for tasks with low promotion potential. However, these observed differences are far from being biologically fixed – ‘gendering’ begins early in life and the evidence shows that preferences and skills are highly malleable. You can influence tastes, and you can certainly teach people to tolerate risk, to do maths, or to negotiate salaries.

What’s more, independently of where they come from, Blau and Kahn show that these empirically observed differences can typically only account for a modest portion of the gender pay gap.

In contrast, the evidence does suggest that social norms and culture, which in turn affect preferences, behaviour and incentives to foster specific skills, are key factors in understanding gender differences in labor force participation and wages. You can read more about this in our blog post dedicated to answer the question ‘How well do innate gender differences explain the gender pay gap?’.

Independently of the exact origin of the unequal distribution of gender roles, it is clear that our recent and even current practices show that these roles persist with the help of institutional enforcement. Goldin (1988), for instance, examines past prohibitions against the training and employment of married women in the US. She touches on some well-known restrictions, such as those against the training and employment of women as doctors and lawyers, before focusing on the lesser known but even more impactful ‘marriage bars’ which arose in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These work prohibitions are important because they applied to teaching and clerical jobs – occupations that would become the most commonly held among married women after 1950. Around the time the US entered World War II, it is estimated that 87% of all school boards would not hire a married woman and 70% would not retain an unmarried woman who married.10

The map here highlights that to this day, explicit barriers across the world limit the extent to which women are allowed to do the same jobs as men.11

However, even after explicit barriers are lifted and legal protections put in their place, discrimination and bias can persist in less overt ways. Goldin and Rouse (2000), for example, look at the adoption of “blind” auditions by orchestras, and show that by using a screen to conceal the identity of a candidate, impartial hiring practices increased the number of women in orchestras by 25% between 1970 and 1996.12

Many other studies have found similar evidence of bias in different labor market contexts. Biases also operate in other spheres of life with strong knock-on effects on labor market outcomes. For example, at the end of World War II only 18% of people in the US thought that a wife should work if her husband was able to support her. This obviously circles back to our earlier point about social norms.13

Strategies for reducing the gender pay gap

In many countries wage inequality between men and women can be reduced by improving the education of women. However, in many countries gender gaps in education have been closed and we still have large gender inequalities in the workforce. What else can be done?

An obvious alternative is fighting discrimination. But the evidence presented above shows that this is not enough. Public policy and management changes on the firm level matter too: Family-friendly labor-market policies may help. For example, maternity leave coverage can contribute by raising women’s retention over the period of childbirth, which in turn raises women’s wages through the maintenance of work experience and job tenure.14

Similarly, early education and childcare can increase the labor force participation of women — and reduce gender pay gaps — by alleviating the unpaid care work undertaken by mothers.15

Additionally, the experience of women’s historical advance in specific professions (e.g. pharmacists in the US), suggests that the gender pay gap could also be considerably reduced if firms did not have the incentive to disproportionately reward workers who work long hours, and fixed, non-flexible schedules.16

Changing these incentives is of course difficult because it requires reorganizing the workplace. But it is likely to have a large impact on gender inequality, particularly in countries where other measures are already in place.17

Implementing these strategies can have a positive self-reinforcing effect. For example, family-friendly labor-market policies that lead to higher labor-force attachment and salaries for women, will raise the returns to women’s investment in education – so women in future generations will be more likely to invest in education, which will also help narrow gender gaps in labor market outcomes down the line.18

Nevertheless, powerful as these strategies may be, they are only part of the solution. Social norms and culture remain at the heart of family choices and the gender distribution of labor. Achieving equality in opportunities requires ensuring that we change the norms and stereotypes that limit the set of choices available both to men and women. It is difficult, but the evidence shows that social norms, too, can be changed.