Oral rehydration therapy is a very simple and cheap treatment which save many lives every day, but it took humanity surprisingly long to realize it.

Here is what we know:

- Over recent decades the number of children dying from diarrheal diseases has fallen very substantially (by two-thirds since 1990).

- Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is a large part of the success story. It is estimated that it saved around 70 million lives since its introduction in the late 1970s.

- ORT is a simple, cheap and effective treatment for a major public health problem.

- Still close to half a million children die every year from diarrheal diseases.

- Increasing the coverage of ORT globally has the potential to save many more lives.

In recent decades the world has made significant progress in reducing the number of deaths caused by diarrheal diseases. 2.6 million people died from diarrheal diseases back in 1990. Since then, the annual number of deaths from diarrheal diseases fell by around one million.

Progress against diarrheal deaths among children has been even more substantial: deaths of children under 5 have fallen by two-thirds since 1990.1

In this post I want to focus on one intervention that has played a large role in reducing child deaths from diarrheal disease across the world and that has the potential to save many more lives in the future: oral rehydration therapy.

Diarrhea can lead to life-threatening dehydration and therefore, an effective treatment needs to target the loss of fluids. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT, also referred to as ORS) is one of the most common treatments used to prevent dehydration caused by diarrhea.2

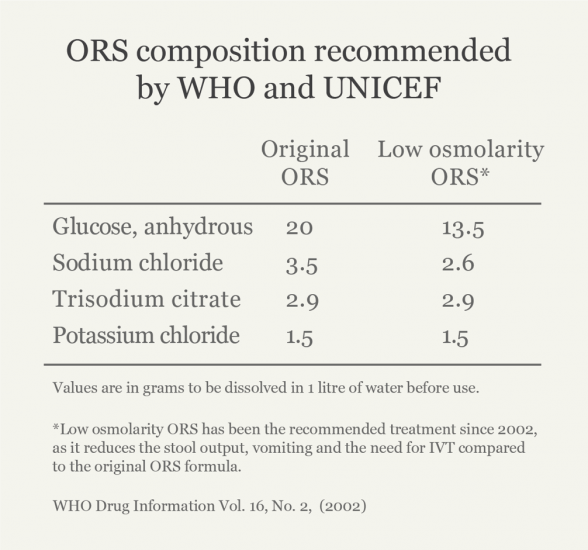

ORT is an incredibly simple therapy: a mixture of water, salt and sugar. It can be administered orally, without the need for special medical assistance. Simple as it may seem, the medical journal The Lancet has called ORT “the most important medical advance of the 20th century”.3

You can read more about the biological mechanism of how ORT works here.

When it comes to “the most important medical advances” and life-saving interventions, we often think about expensive drugs and complicated surgeries that were discovered and perfected in sophisticated laboratories. ORT defies these expectations. Not only is it low-tech and cheap (only around 0.50$ per treatment course), but it was also developed far away from the world’s leading hospitals, under often challenging circumstances.

The early hospital trials for ORT in the late 1960s were performed by Drs Richard Cash and David Nalin in Dacca, in today’s Bangladesh. The most common treatment for diarrhea at the time was the much more expensive intravenous rehydration therapy (IVT), which involved the administration of saline solution intravenously in hospital settings. While IVT was an effective treatment, Cash and Nalin recognized the need for an alternative treatment because the people most affected by diarrheal disease were those who did not have access to clinical centers where IVT was available. In addition, the possibilities of scaling-up IVT use during large outbreaks of diseases – such as cholera epidemics – were limited.

In the late 1960s Cash and Nalin conducted a number of small clinical trials during cholera epidemics in the region, which showed the promise of ORT.4 However, the most significant proof of ORT effectiveness came from desperate circumstances during the Indo-Pakistani War in 1971.5 The conditions of war, complicated by the monsoon season, displaced millions of people into refugee camps, which ultimately led to a disastrous cholera outbreak. Early during the outbreak almost 30% of the afflicted patients died due to the shortage of the IVT therapy. Pressed by the disastrous circumstances, Dr Dilip Mahalanabis decided to start providing bags of salt and sugar dissolved in water to the people in the camp. The decision by Dr Mahalanabis proved to be the right one: in just a few months the case-fatality ratio from cholera and cholera-like diarrheal diseases fell below 4% among the people treated with ORT, as compared with the 30% ratio observed previously. This success was a major stepping stone for wider adoption of ORT.6

While ORT is a simple, low-tech solution for the treatment of diarrhea – a major public health issue – it took many years for its use to be accepted. It wasn’t until 1978 that the World Health Organization (WHO) created the diarrheal disease control program that has helped to popularise the use of ORT worldwide.7 To put this into perspective – we only adopted the use of ORT more than a decade after we landed on the Moon.

There are many reasons why the uptake and recognition of ORT by richer countries was slow. Western doctors were skeptical of adopting treatments tested in developing countries and considered these to be of a lower standard.8 The idea that drinking a simple water, sugar, and salt solution, was just as good of a treatment as a “sophisticated” intravenous drip seemed radical at the time. And, even today, ORT treatment seems counterintuitive, because, while it reduces the likelihood of death and speeds up recovery, it does not actually prevent or stop diarrhea.

How many lives has ORT saved? The exact number is in some ways impossible to know because many other interventions and treatments have contributed to the decreasing number of deaths from diarrheal diseases. However, the incredible decline in deaths from diarrheal diseases in children in the last two decades of the 20th century (from around 4.8 million annual deaths in 1980 to 1.2 million deaths in 2000) has coincided with an expanded global use of ORT. A number of researchers have suggested that the dramatic decline was not just a coincidence but directly caused by the increased ORT use.9 Twelve years ago Fontaine, Garner, and Bhan estimated that more than 50 million children have been saved by ORT between 1982 and 2007 – that is on average of 2 million lives a year.10 Based on these estimates the number of children saved from 1982 until 2019 by ORT could be more than 70 million. Whatever the exact number of lives saved is, it would not be an overstatement to say that many adults would not be alive today if not for the discovery of ORT.

But ORT can still do more. In our related post we take a look at how far ORT could go: what are the barriers to it saving more lives, and how many could it save?