Humanity’s history is a continuous battle between us and the microbes.1 For most of our history we were on the losing side.

It wasn’t even close. We were losing very decisively. Billions of children died from infectious diseases. They were the main reason why child mortality was so high: No matter where or when they were born, around half died as children. We looked at the evidence of child mortality in pre-modern times here.

The recurring epidemics of influenza, measles, cholera, diphtheria, the bubonic plague, and smallpox also killed large parts of the adult population. Within just a few years the Black Death killed half of Europe’s population.2 The epidemics – especially of smallpox, but also measles, typhus and other diseases – that the colonialists brought from Europe with them to the Americas often killed an even larger share of the population.3

The world today is obviously very different. Infectious diseases are the cause of fewer than 1-in-6 deaths, and as the world made progress against the microbes our lives became much longer. The global average life expectancy is now 73 years after life expectancy doubled in every world region.

Until recently no one knew where diseases came from

How is it possible that for millennia we were losing the battle against the microbes so awfully and then turned things around in the span of just a few generations?

Science is the foundation for our success. 150 years ago nobody knew where diseases came from. Or more precisely, people thought they knew, but they were wrong. The widely accepted idea at the time was the ‘Miasma’ theory of disease. Miasma, the theory held, was a form of “bad air” that causes disease. The word malaria is testament to the idea that ‘mal aria’ – ‘bad air’ in medieval Italian – is the cause of the disease.

Thanks to the work of a number of doctors and chemists in the second half of the 19th century humanity learned that not noxious air, but specific germs cause infectious diseases. The germ theory of disease was the breakthrough in the fight against the microbe. Scientists identified the pathogens that cause the different diseases and thereby laid the foundation for perhaps the most important technical innovation in our fight against them: vaccines.

Vaccines get your immune system ready for the battle

Vaccines protect us from infectious diseases by offering our body a training session for how to fight the germs that cause the disease. “The fundamental idea of a vaccine is deliberate exposure to a relatively harmless or dead version of a germ. The immune system will then recognise and eliminate that germ rapidly if it is encountered again,” as vaccine developer Richard Moxon puts it.4

The trick is that the ineffective form of the pathogen is not causing the disease, but resembles the effective pathogen so much that it triggers our body’s natural immune system to produce the antibodies that destroy that pathogen. The training session that it provides to the body means our immune system will recognize the invader once we become infected with the real pathogen later in life. Our immune system can quickly muster up what it learnt from the vaccine response, and immediately start fighting the pathogen.

Public health: You are only safe if everyone else is safe

Vaccines not only protect the health of the immunized person but also the health of the community. If vaccination rates are high enough the transmission of infectious diseases is interrupted in the community which means that even those who are unvaccinated gain protection.

As is so often the case in development you cannot achieve progress by yourself. Your progress towards a healthier life depends on everyone else’s progress towards a healthier life; you safer if others are vaccinated too. The health improvements that you cannot achieve by yourself is the sphere of public health and many of the most important interventions in the fight against infectious diseases were therefore financed socially. Public spending financed the crucial improvements in sanitation as well as many large vaccination programs.

Vaccination programs are one of many strategies by which we made progress against infectious diseases. The first pathogen successively defeated by humans in Europe – as early as the 17th century – was the plague. According to Shaw-Taylor (2020) this was achieved by a combination of quarantine measures, cordons sanitaire and contact tracing (which was first developed in the Renaissance).5

Since then we found many additional strategies against the various microbes. Antibiotics, safe drinking water, better housing, better education, falling poverty, declining undernourishment, pasteurization, hygiene, better sanitation and other public health advancements were and are crucial. Jason Crawford provides an excellent overview of the crucial role of better sanitation, hygiene, and other public health measures for the progress since the 19th century.

Today too, vaccines are only one of many strategies that we have found in the battle against the microbes. We see now – in the COVID-19 pandemic – that there are several countries responding successfully to the virus without the help of a vaccine (we studied how they do this here).

How effective were these training sessions against infectious diseases?

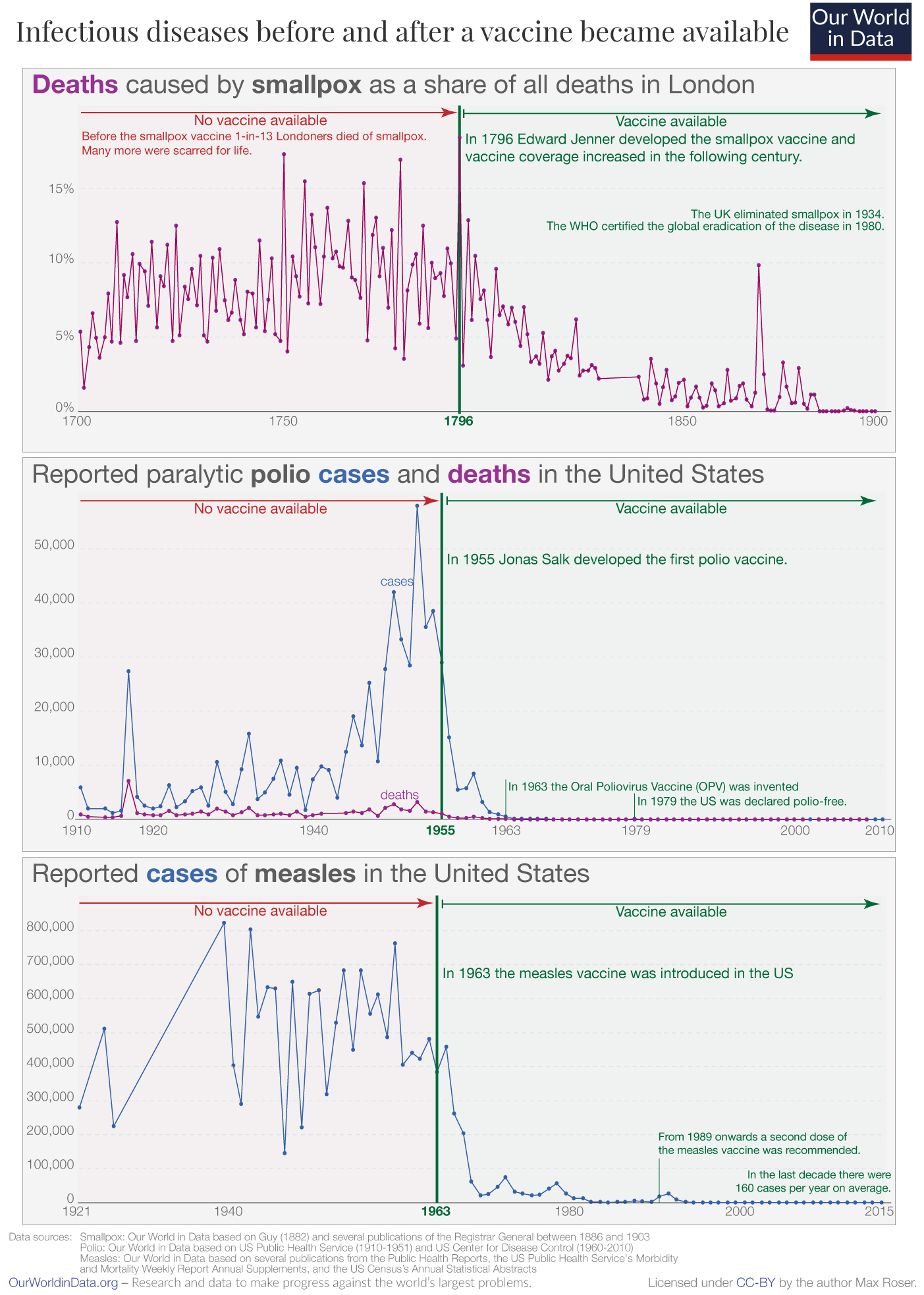

In the three charts I plotted the evolution of three infectious diseases over several decades. You see the data before and after the first vaccination became available.

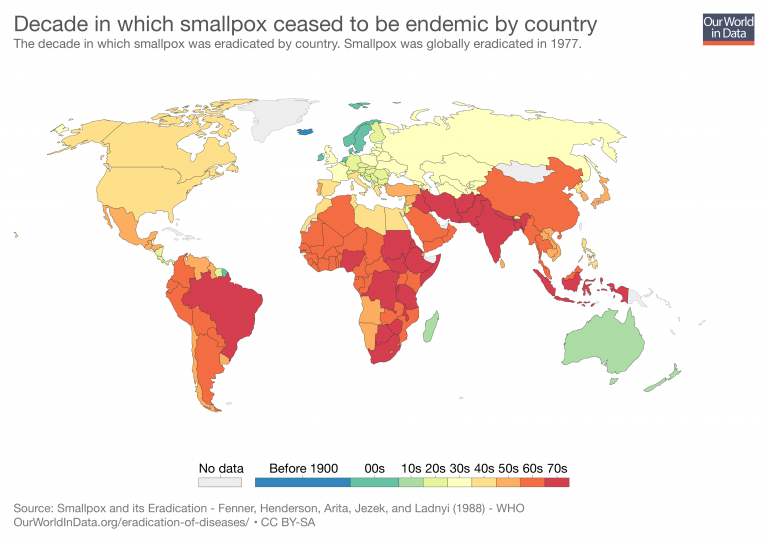

Smallpox was one of the worst killers in our history. Epidemiologist Donald Henderson suggests that in the last hundred years of its existence smallpox killed at least half a billion people.6 Even more people were disfigured by the disease for the rest of their lives.7 Despite all efforts, humanity never found an effective treatment. But we invented something even better: a vaccine, the very first vaccine ever.

In England in the mid‐eighteenth century it was probably the leading cause of death.8 But in the following century – as the vaccine reached more people and improved over time – it became rarer and rarer as a cause of death.

Eventually the disease was eliminated in entire countries, then entire continents, and today the disease does not exist anywhere in the world. The smallpox vaccine made it possible to completely eradicate the disease. Its eradication has saved the lives of around 150 to 200 million people since.

The history of polio is similar, but more recent. Polio epidemics spread panic at a time that many today can still remember. Polio is an infectious disease, contracted predominantly by children, that can lead to the permanent paralysis of various body parts. Ultimately it can cause death by immobilizing the patient’s breathing muscles.

The chart shows data from the US, the country where the first vaccine was developed and used. In the first half of the last century the US suffered large outbreaks with many tens of thousands paralyzed. Patients’ only chance to survive was to be confined to a large, mechanical breathing apparatus: the so-called ‘iron lungs’.

The recurring outbreaks ended in 1955 when Jonas Salk finally developed the polio vaccine. When it was announced on April 12 it was celebrated as “more than a scientific achievement” according to Salk’s biographer Richard Carter.9. The vaccine, he writes, “was a folk victory, an occasion for pride and jubilation… people observed moments of silence, rang bells, honked horns, blew factory whistles, fired salutes,… took the rest of the day off, closed their schools or convoked fervid assemblies therein, drank toasts, hugged children, attended church, smiled at strangers, and forgave enemies.”

As the chart shows, these celebrations were not misplaced. Over the coming years vaccination campaigns reached many American children and the terrible epidemics ended. By 1979 the US was declared polio-free.

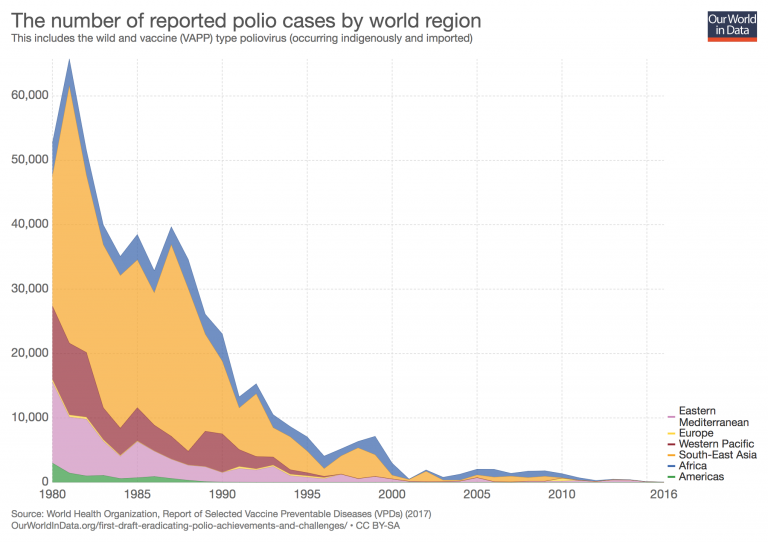

Today our generation has the chance to achieve for polio what has been achieved for smallpox: eradicate it completely. Thanks to the vaccine, humanity has made massive progress towards this goal. In the early 1980s there were between three- and four-hundred-thousand paralytic cases every year. In the last 12 months (as the time of writing) there were 298 polio cases globally.10

Measles too was a major killer for many centuries. The WHO reports: “Before the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963 and widespread vaccination, major epidemics occurred approximately every 2–3 years and measles caused an estimated 2.6 million deaths each year.”11

Measles is both very deadly and extremely contagious. Published estimates of the basic reproduction number (R0) – the average number of secondary cases arising from each case – range from 3.7 up to 203.12

The chart shows how rapidly we made progress against this killer after the invention of the vaccine. Once it was introduced in the US, the large outbreaks of the airborne disease came to an end. The measles vaccine too changed world history and the history of millions of families.

Globally we have also made a lot of progress. Today, 85% of one-year olds receive the measles vaccine and the number of deaths has fallen from 2.6 million to 83,000 in the latest data.

Smallpox, polio, and measles are just three of the diseases we have vaccines for. We now have effective vaccines against at least 28 diseases.13

I selected these three diseases because they protect us from particularly terrible diseases. And the vaccines for polio and measles stand out because even the very early stage prototypes were very efficacious; the efficacy of many other vaccines increased slowly over time as researchers made adjustments that improved them.

Some of the best training you ever received were the vaccines you were given in your very early childhood. Without even realizing it, you learned how to battle the pathogens that ravaged the lives of your ancestors for many millennia.

When humanity achieves very substantial progress it can become difficult to understand what the problems were that we made progress against. This is also the case for vaccine-preventable diseases. Infectious diseases that once disfigured, pained, paralyzed, and killed many of our ancestors have disappeared so far from our lives and memories that some today can afford the luxury of disregarding or even avoiding vaccination.

Today as we face the COVID-19 pandemic, it is the first time for many of us that we experience for one infectious disease what our ancestors experienced for a whole range of them. Just as they were without protection against the diseases discussed previously, we are now facing a pathogen that we have no treatment for and no protection from.

And now, just as back then, our best hope is science. The responses from South Korea, Vietnam, and Germany show that it is possible to fight the disease successfully, but to end the suffering that COVID-19 causes our best hope is a vaccine against the virus.

We were never better equipped to battle a virus. The genome was sequenced within two weeks and since then scientists around the world have been working tirelessly to develop the vaccine that brings the pandemic to an end. The early results from the vaccine developed here at the University of Oxford are promising.

Our best strategy in the age-old fight against the germs is our collaborative, data-based effort to study the world around us and within us. Our best strategy is science.

…continue reading on Our World in Data: