Globally, seasonal influenza kills 400,000 people from respiratory disease each year on average. During large flu pandemics, when influenza strains evolved substantially, the death toll was even higher.

But the risk of dying from influenza has declined substantially over time from improvements in sanitation, healthcare, and vaccination.

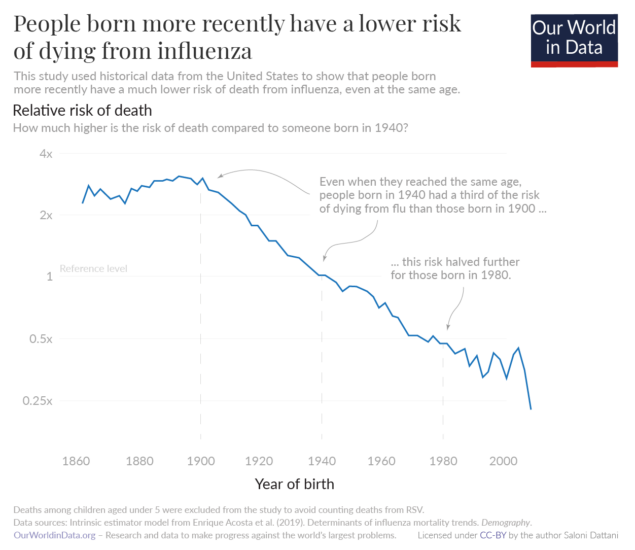

People born in 1940 had around a third of the risk of dying from influenza as those born in 1900 – even when they reached the same age. This decline continued, and those born in 1980 have a risk of half that of those born in 1940.

Influenza still remains a large burden around the world, because of an aging population and a lack of access to healthcare and sanitation in many countries.

In this article, we look into these developments in detail: how many people die from seasonal influenza and how this has changed over time.

We will also look at which factors increase the risk of dying from the flu and understand why, in some years, influenza has led to large pandemics that caused millions of deaths. This knowledge can inform us about the risks of influenza in the future.

Although this is an important question, it is often difficult to answer.

Despite being a well-understood disease, it can be hard to count the number of deaths from influenza for several reasons.1

One problem is that the symptoms of influenza look similar to other infections, such as respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus. In many countries, only a fraction of patients with an “influenza-like illness” are tested to confirm whether they were infected by the virus.2 This means we miss many – or, in some countries, most – infections.

Another problem is that influenza can lead to death in a number of indirect ways. It can cause death through respiratory complications such as pneumonia, but also from cardiovascular complications such as heart attacks and strokes, or other serious infections. This is especially true for the elderly and people who have chronic health conditions.3 Without accounting for these deaths, we would underestimate the number of flu deaths.

To overcome this, researchers estimate the burden of influenza with other methods. They can estimate the number of excess deaths that occur during flu seasons, and use routine surveillance data and mortality records, to estimate how many of these are caused by the flu.

The annual mortality caused by seasonal influenza was estimated by the Global Pandemic Mortality Project II using data between 2002 and 2011. They estimated that, during this period, seasonal influenza caused between 294,000 and 518,000 deaths each year globally.4

These estimates focus on deaths where people had respiratory disease. This means they miss some flu deaths, as some people may die from cardiovascular complications of the flu without having respiratory disease.5

On the map, you can see the estimates of flu mortality shown as a rate per 100,000 people, among people aged over 65.

In Europe, the rate of deaths from the flu was 30.8 per 100,000 each year, among those aged over 65. This is more than three times the risk from traffic accidents, which kill 9 per 100,000, in the same age group.6

In low-income countries, these estimates tend to be less certain, due to lower levels of testing for influenza and limited mortality records.

But flu is estimated to be more deadly in countries in South America, Africa, and South Asia than in Europe and North America. For example, Indonesia has more than twice the death rate of Canada. These disparities are at least partly due to poverty, poorer underlying health, and lower access to healthcare.

Death rates from influenza are much lower than they were in the past.

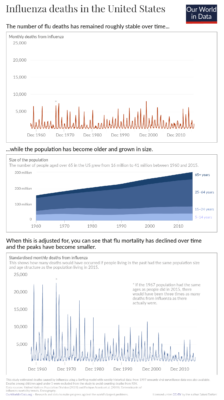

We don’t have good long-term estimates of flu deaths across most countries. But, researchers have produced weekly estimates of influenza deaths over long periods in the United States. This allows us to see how modern rates compare to the past. You can see this data in the chart.7

Deaths from influenza fluctuate across the year, with large peaks in the winter.8 The total number of deaths from influenza has been roughly stable in the United States over the last 65 years. You can see this in the top panel of the chart.

However, a large part of this is due to the fact that the population has been growing and aging.

If we look at death rates within age groups, the rate of deaths from influenza has been falling. You can see this in the bottom panel, which accounts for changes in the size and age structure of the population.

This means the likelihood that someone dies from influenza at a given age has declined over time. But, because the population is getting larger and older, the total number of deaths has remained stable.

Influenza mortality has declined over several generations. We know this from historical data from the United States, which has been used to estimate “cohort effects”. This tells us whether people who were born more recently have lower risks of death, after accounting for their younger age.

Since 1900, there has been a long-term decline in the risk of dying from the flu.9 There are several reasons for this.

One is that there were large projects to improve sanitation in cities across the United States in the early 1900s.10 Over the twentieth century, there were also improvements in neonatal healthcare and increases in the rate of childhood vaccinations. All of these factors had benefits that carried forward as people aged: they protected people from developing comorbidities that increased the risk of dying from influenza.

There has also been an increase in the rate of flu vaccinations. Influenza vaccines were developed for the first time in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1952, the World Health Organization began a surveillance system to monitor which flu strains were circulating worldwide. This helped researchers develop new vaccines each year that matched those strains.11 Over the following decades, the rate of influenza vaccinations among the elderly began to grow.12

The historical decline in influenza mortality has been substantial, as you can see in the chart.

Even when they reached the same age, people born in 1940 had around a third of the risk of dying from influenza as those born in 1900. This decline continued, and those born in 1980 had a risk of half that of those born in 1940.13

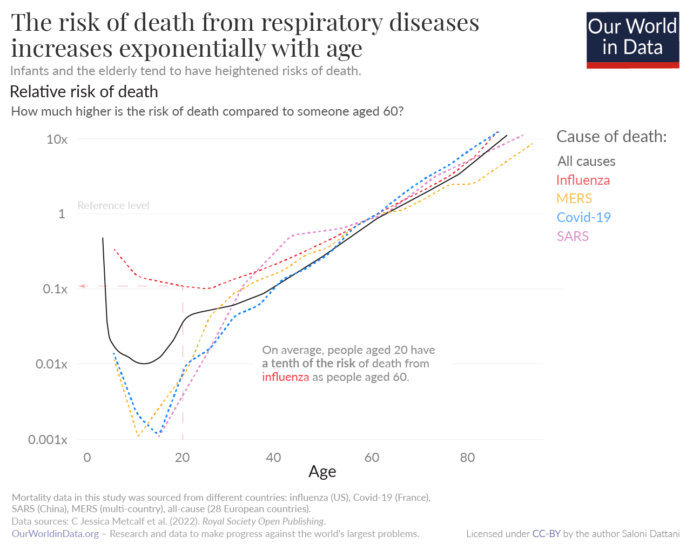

Age is a major risk factor of dying from the flu. As you can see in the chart, infants and the elderly tend to have a much higher risk of death from a range of respiratory diseases, including influenza, compared to young adults. For example, 60-year-olds have a ten times greater risk of death from influenza than 20-year-olds.14

Once someone reaches their twenties, their mortality risk from the flu increases exponentially. This shape follows the risk of death from all causes.15

The risk of dying from influenza also depends on other factors such as the quality of healthcare, the strain of influenza, and whether the person received the flu vaccine.16

Every year, influenza vaccines are reformulated to match the strains of flu that are expected to dominate during the winter. When there is a mismatch between the strains in the vaccine and the flu strains that are circulating, the vaccines tend to have lower efficacy, and flu seasons tend to be more severe.17

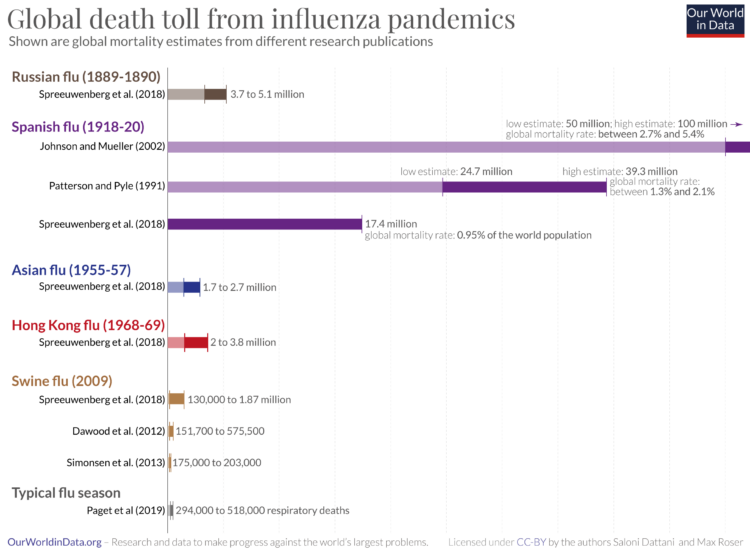

Some seasons are far more severe than usual seasonal influenza. This tends to occur when new influenza strains arise and cause influenza pandemics.

Over time, influenza viruses that are circulating in the population tend to mutate through a process called “antigenic drift”. This gives them the ability to evade people’s immunity.

But, influenza viruses can also evolve with large and sudden changes. This happens in a process called “antigenic shift”, when parts of different strains combine with each other. These new combinations can be more infectious and lethal than previous strains, leading to deadlier pandemics.

For example, the Spanish flu evolved from a combination of human influenza and another animal influenza, which formed a new H1N1 influenza virus. As you can see in the chart, it caused the largest influenza pandemic in history: research by Spreeuwenberg et al. (2018) suggests that the Spanish flu killed around 17.4 milion people. Other estimates are even higher: Johnson and Mueller (2002) suggest that the Spanish flu killed between 50 to 100 million people.18

This death toll massively exceeds the number who die in a typical year from the flu – it is between 30 to 340 times higher than the estimate of 294,000 to 518,000 deaths that are caused by seasonal influenza each year, even though the global population was much smaller at the time.19

Mortality during the Spanish flu rose sharply in young adults, compared to previous seasons. Research suggests that this is because they lacked immunity to H1 influenza viruses because they had been exposed to different influenza strains in their childhood. In contrast, older generations had been exposed to similar H1 influenza viruses decades before the pandemic began, which gave them some protection from the H1N1 pandemic strain.20

Seasonal flu causes 400,000 respiratory deaths each year on average. But the burden is far lower than it was in the past, due to improvements in sanitation, healthcare, and vaccination.

The flu also remains a large burden around the world for two major reasons. One is that many people around the world still lack access to healthcare and have low rates of influenza vaccination, which increases the risk of death.

Another reason is that the populations of many countries have been aging rapidly. In lower-income countries, the flu could become a larger burden as they face aging populations in the future.

To tackle this risk, the world can take lessons from how the burden has been reduced in the past. One way is to increase the rates of influenza vaccination, as well as other routine vaccinations, which also reduce the risk that flu is severe. Another is to improve sanitation and access to healthcare around the world.

We’ve already seen a huge decline in the burden of the flu over many decades, and with greater efforts, we could see that burden decline even further.

Keep reading on Our World in Data:

Acknowledgments: Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser and Edouard Mathieu provided very helpful guidance and comments that helped improve this post.