Introduction

In almost every country in the world, men are more likely to participate in labor markets than women. However, these gender differences have been narrowing substantially, and in most countries around the world the share of women who are part of the labor force is higher today than half a century ago. In this blog post we discuss the key factors driving this change (for an in-depth look at the change itself, including key facts and trends, see our companion blog post).

In order to understand changing female labor force participation, it is important to first conceptualize the overarching context within which various factors operate. For women to be able to participate in the labor market, they have to have the time and opportunity to do so. This means that we can only fully analyze labor force participation if we understand time allocation more generally. In the case of female labor supply in particular, time allocation is crucially affected by the fact that women all over the world tend to spend a substantial amount of time on activities such as unpaid care work, which fall outside of the traditional economic production boundary. In other words, women often work but are not regarded as ‘economically active’ for the purpose of labor supply statistics.

Across all world regions, women spend more time on unpaid care work than men. On average, women spend between three and six hours on unpaid care work per day, while men spend between half an hour and two hours. If we consider the sum of paid and unpaid work, women tend to work more than men – on average, 2.6 extra hours per week across the OECD.1

It is therefore not surprising that the factors driving change in female labor supply – whether they are improvements in maternal health, reductions in the number of children, childcare provision, or gains in household technology – all affect unpaid care work. Because time allocation is gendered in this way, female participation in labor markets tends to increase when the time-cost of unpaid care work is reduced, shared equally with men, and/or made more compatible with market work. Crucially, this analysis is not intended to diminish the importance of unpaid care work. On the contrary, such work is fundamental to – rather than separate from – economic activity and wellbeing, and the fact that it is omitted from national accounts is a point of debate.2

With this said, an obvious question remains: why do women perform a disproportionate amount of unpaid care work in the first place? As we discuss below, although time-use should be a choice, evidence shows that social norms play a large part in determining gender roles and consequently, gendered time-use.

Keeping this context in mind, let’s have a look at the evidence behind the ‘drivers’ of rising female labor force participation.

Maternal health

The various aspects related to maternity – pregnancy, childbirth, and the period shortly after childbirth – impose a substantial burden on women’s health and time. This, in turn, can have a significant impact on women’s ability to participate in the labor force.

Before 1930, maternal mortality was the second biggest cause of death for American women in their childbearing years, claiming 850 deaths for every 100,000 live births in 1900. And for each such death, 20 times as many mothers experienced pregnancy-related health conditions which often included long-lasting or chronic disability.3 While maternal mortality has dropped to 10 deaths per 100,000 births across most rich countries, it is still comparatively high in poorer countries. Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, had a rate of 547 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015. (For more information on maternal health, see our entry on Maternal Mortality.)

In a recent study, researchers Albanesi and Olivetti (2016)4 consider how improvements in maternal health between 1930 and 1960 contributed to rising female labor force participation in the US during that time period. Their approach is based on a calibrated macroeconomic model of household behavior. In other words, the authors incorporate numerical measures of medical progress into a quantitative model to assess the role of improving maternal health in accounting for the rise in labor force participation of married women in the US.

To measure ‘medical progress’, Albanesi and Olivetti draw on historical data and use it to estimate the burden of maternal conditions using the concept of ‘disability-adjusted life years’, or DALYs (you can find more details about this concept in our entry on Burden of Disease). Their estimates suggest that the time lost to disabilities associated with maternal conditions declined from 2.31 years per pregnancy in 1920 to 0.17 in 1960. According to their model, the historical decline in the burden of maternal conditions and the introduction of infant formula can account for approximately 50 percent of the increase in married women’s labor force participation between 1930 and 1960 in the US.

The chart here plots US maternal mortality and female labor force participation as an index to their respective values in 1900 (thus 1900 = 100). As we can see, the correlation is stark: maternal mortality declines steeply between 1930 and 1960, during which period female labor force participation rises rapidly. (To see this relationship in a connected scatterplot displaying the raw data for both indicators, see here.)

The number of children per woman

On average, mothers around the world continue to spend more time on childcare than fathers. Because of this, fewer children per woman – lower fertility rates – can theoretically free up women’s time and contribute to an increase in female labor force participation.

The chart here shows the average annual change in fertility and female labor force participation across the world, from 1960 to the most recent year. Despite some outliers and some clear differences by region, we can see that most countries are in the upper-left quadrant – that is, in most countries female labor force participation has gone up at the same time that fertility has gone down.

However, correlation is not the same as causation: a woman’s choice to have fewer children might be influenced by the rising female labor force participation itself or other factors driving it. Instead, causal evidence can be found in studies that have identified exogenous – in other words, externally caused – changes in family size and measured their impact on labor market outcomes.

Some such studies provide evidence from twins, as conceiving twins can be seen as an unexpected increase in fertility.5 Other studies have considered women who sought medical help in achieving pregnancy. In those cases, fertility treatments create a ‘control group’ of women who were unable to become pregnant and a ‘treatment group’ of those who were able to get pregnant.6 And yet other studies have used country-level policies, such as abortion legislation, as an exogenous source of variation in fertility. When available, abortion can be seen as a way to avoid unwanted childbirth, and researchers argue that the timing of policy shifts making abortion legal and available is exogenous.7

In all of these studies, researchers find strong evidence of a causal link between higher fertility rates and lower labor market participation. In the most recent of the studies, Lundborg, Plug and Rasmussen (2017)8 find that women who are successfully treated by in vitro fertilization (IVF) in Denmark earn persistently less because of having children. This decline in annual earnings is explained by the fact that women tend to work less when their children are young and in turn get paid less when their children are older.

But of course, while ‘exogenous variation’ in the number of children per woman is an important way to establish causality, what actually matters is how women’s control over their reproductive choices affects labor market outcomes. In their widely cited 2002 paper, “The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career and Marriage Decisions”, Goldin and Katz (2002)9 examine the behavioral effect of increasing women’s control over their fertility. Their research shows how the diffusion of the birth control pill in the US during the late 1960s contributed to changing women’s career and marriage choices by eliminating the risk of pregnancy, encouraging career investment, and “enabling young men and women to put off marriage while not having to put off sex.”

Childcare and other family-oriented policies

The fact that falling fertility rates lead to higher labor force participation for women is certainly important from an empirical point of view. But it is obviously contradictory to promote female agency while suggesting women should have fewer children.

So it is helpful to consider other factors that make employment compatible with childbearing and thus broaden the choices available to women. Let’s begin with childcare, parental leave, and other family-oriented policies.

While the years after World War II saw a rise in women’s labor force participation across every OECD country, growth in participation began at different points in time, and proceeded at different rates in each country. In 2016, for example, Sweden’s female labor force participation rate was 70%, while it was only 56% in Germany and 40% in Italy. Researchers comparing broad policy configurations argue that the different types of welfare states that emerged in rich countries after World War II have contributed to these differences.10

Social democratic policies such as those seen in Sweden, for example, are characterized by subsidized childcare, paid parental leave that is designed to encourage both mothers and fathers to participate in childcare, and support for full employment. Liberal welfare states, on the other hand, take a more hands-off approach to social policy – one prominent example is the US’s maternity leave, which guarantees only 12 weeks of unpaid annual leave.

In the chart here, we show that female employment, measured as the employment-to-population ratios for women 15+, tends to be higher in countries with higher levels of public spending on family benefits (i.e. child-related cash transfers to families with children, public spending on services for families with children, and financial support for families provided through the tax system, including tax exemptions).

And while the pattern seen in this chart is only a correlation, evidence suggests that this relationship is in fact causal. A natural experiment from Canada, for example, provides compelling proof that childcare support can have a positive effect on the labor force participation rate of mothers with young children. In 1997, the provincial government of Quebec introduced a generous subsidy for childcare services, effectively imposing an exogenous reduction in childcare prices. Researchers Lefebvre and Merrigan (2008)11 found that this policy had substantial labor supply effects on the mothers of preschool children, both among well-educated and less well-educated mothers. In 2002, the policy increased the participation rate of mothers (with at least one child aged 1-5 years) by 8 percentage points, and their hours worked increased by 231 per year.

Labor-saving consumer durables

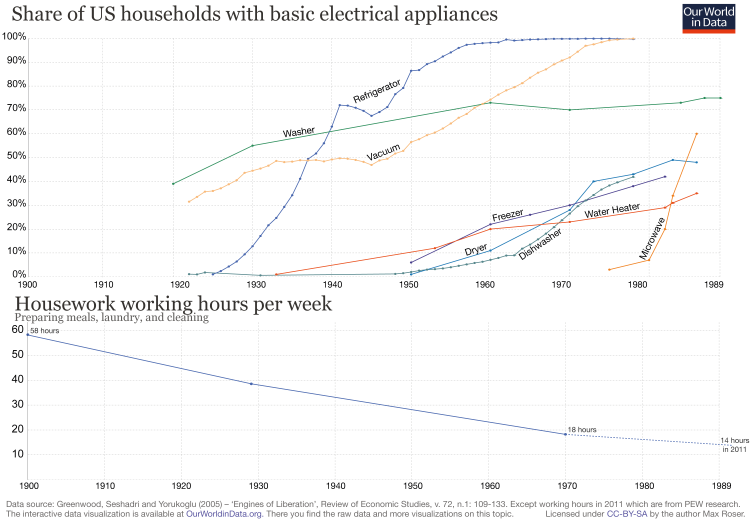

In 1890, only 24% of US households had running water. In 1900, 98% of households in the US washed their clothes using a scrubboard and water heated on a wood or coal-burning stove. It is not hard to see then why in 1900, the average American household spent 58 hours per week on housework. By 1975, that figure had declined to 18. Progress in labor-saving consumer durables in the household has thus been another factor contributing to the rise in female labor force participation, especially in early-industrialized countries. Of course, this is feasible especially because women – both in 1900 and now – take on a disproportionate amount of unpaid domestic work.

Greenwood et al. (2005)12 present evidence for this by calibrating a quantitative economic model to show that the consumer goods revolution – which, as we can see in the chart here, introduced washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and other time-saving products – can help explain the rise in married female labor force participation in the US.

It is important to know, however, that these improvements have not yet reached all households around the world. 9% of the global population (about 663 million people) are still without access to improved water sources. A recent study by Graham, Hirai, and Kim (2016)13 looked at water-collection in Sub-Saharan Africa – where it is estimated that more than two-thirds of the population must leave their home to collect water – and found that this time-consuming and physically grueling chore falls primarily to women.14

Social and cultural factors

Some argue that there is a “natural” distribution of gender roles, with women being better suited to domestic and child-rearing responsibility and men to working outside of the home. Such assertions lack compelling evidence and more importantly, perpetuate a status quo that limits the choices available to both men and women.15 Instead, it is known that social norms and culture influence the way we see the world and our role in it. To this end, there is little doubt that the gender roles assigned to men and women are in no small part socially constructed.16

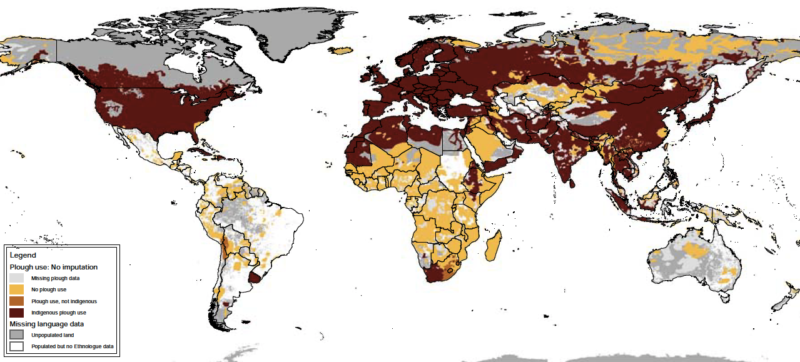

To determine when and how existing gender norms first gained a foothold, researchers have attempted to connect historical evidence to modern norms and opinions.17 For example, Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013)18 contribute to the explanation of existing cross-cultural beliefs and values about the appropriate role of women in society by looking at the division of labor in the distant past. They test the hypothesis that historically, societies that adopted plough-based agriculture, which required “significant upper body strength”, gave men an advantage relative to women in a crucial aspect of production. They contrast such societies to those that employed ‘shifting cultivation’, which uses hand-held tools like the hoe, and which women participated actively in.

Their findings suggest that the division of labor that arose around plough-use generated persistent cultural norms about the appropriate role of women in society, which norms have continued to exist at an individual level beyond agrarian economies and under different institutional structures. By comparing pre-industrial ethnographic data with contemporary measures of individuals’ views on gender roles across countries, ethnic groups, and individuals, they show that historical plough use has a positive statistical relationship with unequal gender roles today.

They construct a map, shown here, which approximates the global distribution of languages and historical plough use for each group. This data is used to show a correlation between historical plough use and lower female participation in the labor force today.

Global distribution of languages and historical plough use – Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013)19

Another study published in the journal Science by Dyble et al. (2015),20 goes even further back in time, arguing that hypercooperation among hunter-gatherers – an important characteristic that may serve to evolutionarily differentiate modern humans from our ancestors – was enabled by sex egalitarianism. The study uses agent-based modeling to suggest that wealth and sex inequalities began to emerge when “heritable resources, such as land and livestock, became important determinants of reproductive success.”

And while it is possible that socially-assigned gender roles emerged in the distant past, our recent and even current practices show that these roles persist with the help of institutional enforcement. Goldin (1988),21 for instance, examines past prohibitions against the training and employment of married women in the US. She touches on some well-known restrictions, such as those against the training and employment of women as doctors and lawyers, before focusing on the lesser known but even more impactful “marriage bars” which arose in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These work prohibitions are important because they applied to teaching and clerical jobs – occupations that would become the most commonly held among married women after 1950. Around the time the US entered World War II, it is estimated that 87% of all school boards would not hire a married woman and 70% would not retain an unmarried woman who married.

The map here shows that to this day, legal barriers to female labor force participation exist in parts of the world. The data in this map, which comes from the World Bank, provides a measure of whether there are any specific jobs that women are not allowed to perform. So, for example, a country might be coded as “No” if women are only allowed to work in certain jobs within the mining industry, such as health care professionals within mines, but not as miners.

But even after explicit barriers are lifted and legal protections put in their place, discrimination and bias can persist in less overt ways. Goldin and Rouse (1997),22 for example, look at the adoption of “blind” auditions by orchestras, and show that by using a screen to conceal the identity of a candidate, impartial hiring practices increased the number of women in orchestras by 25% between 1970 and 1996.

In fact, discrimination and biases operate in many other ways, permeating all spheres of life. As the chart here shows, at the end of World War II, only 18% of people in the US thought that a wife should work if her husband was able to support her. Indeed, it is not surprising that around this time, female labor supply in market activities was low, and demand-side barriers were high. As this chart shows, female labor supply started increasing in the US alongside changing social norms: people’s approval of married women working went up during a period of remarkable growth in female labor force participation, and then flattened at around the same time that participation stalled. For more details on this see Fortin (2015)23 and Goldin and Katz (2016)24.

Social norms and culture are clearly important determinants of female labor force participation. So how can social norms be changed? Research in this area shows that social norms and culture can be influenced in a number of non-institutional ways, including through intergenerational learning processes, exposure to alternative norms, and activism such as that which propelled the women’s movement.25

Structural changes in the economy

Having now discussed the various determinants affecting women’s labor force participation in the context of socially-assigned gender roles, we turn to the larger picture. How do these pieces factor into a global landscape of varied income levels and changing economic conditions?

In low-income countries, where the agricultural sector is particularly important for the national economy, we see that women are heavily involved in production, primarily as family workers. Under such circumstances, productive and reproductive work is not strictly delineated and can be more easily reconciled. With technological change and market expansion, however, work becomes more capital intensive and is often physically separated from the home. In middle income countries, there is an observed social stigma attached to married women working and “women’s work is often implicitly bought by the family, and women retreat into the home, although their hours of work may not materially change.”26

With sustained development, women make educational gains and the value of their time in the market increases alongside the demand-side pull from growing service industries. This means that in high income countries, the rise in female labor force participation is characterized by women gaining the option of moving into paid, often white-collar work, while the opportunity cost of exiting the workforce for childcare rises.27

The chart here shows some evidence of this pattern. As we can see, female labor force participation is highest in some of the poorest and richest countries in the world, while it is lowest in countries with incomes somewhere in between. In other words: in a cross-section, the relationship between female participation rates and GDP per capita follows a U-shape.

Given that informal employment in the agricultural sector is typically not captured in labor statistics, the chart here offers only partial evidence of the mechanisms described above. However, multiple studies have found support of a U-shaped female labor supply function, both within and across countries over the course of development.28

Closing remarks

The rise in female labor force participation has been one of the most notable economic developments of the past century. In many countries, this change has been driven by the large and sustained increase in married women’s labor force participation.

There is good reason for this. In the context of ‘private’ family life, social norms across the world have long dictated that women should perform unpaid care work – taking care of children and elderly parents, making meals, doing laundry, maintaining family relations – while men engage in market work. Therefore, the factors that have given married women the option to enter the labor force are foreseeably those that have lowered the time-cost of unpaid care work or made employment more compatible with it.

Of course, this is not to say that unpaid care work is unimportant: it is a crucial, albeit unrecorded, aspect of economic development and wellbeing. Rather, the hope is that with sustained social change, neither women nor men will be obliged to make decisions about time allocation on the basis of their sex.