Summary

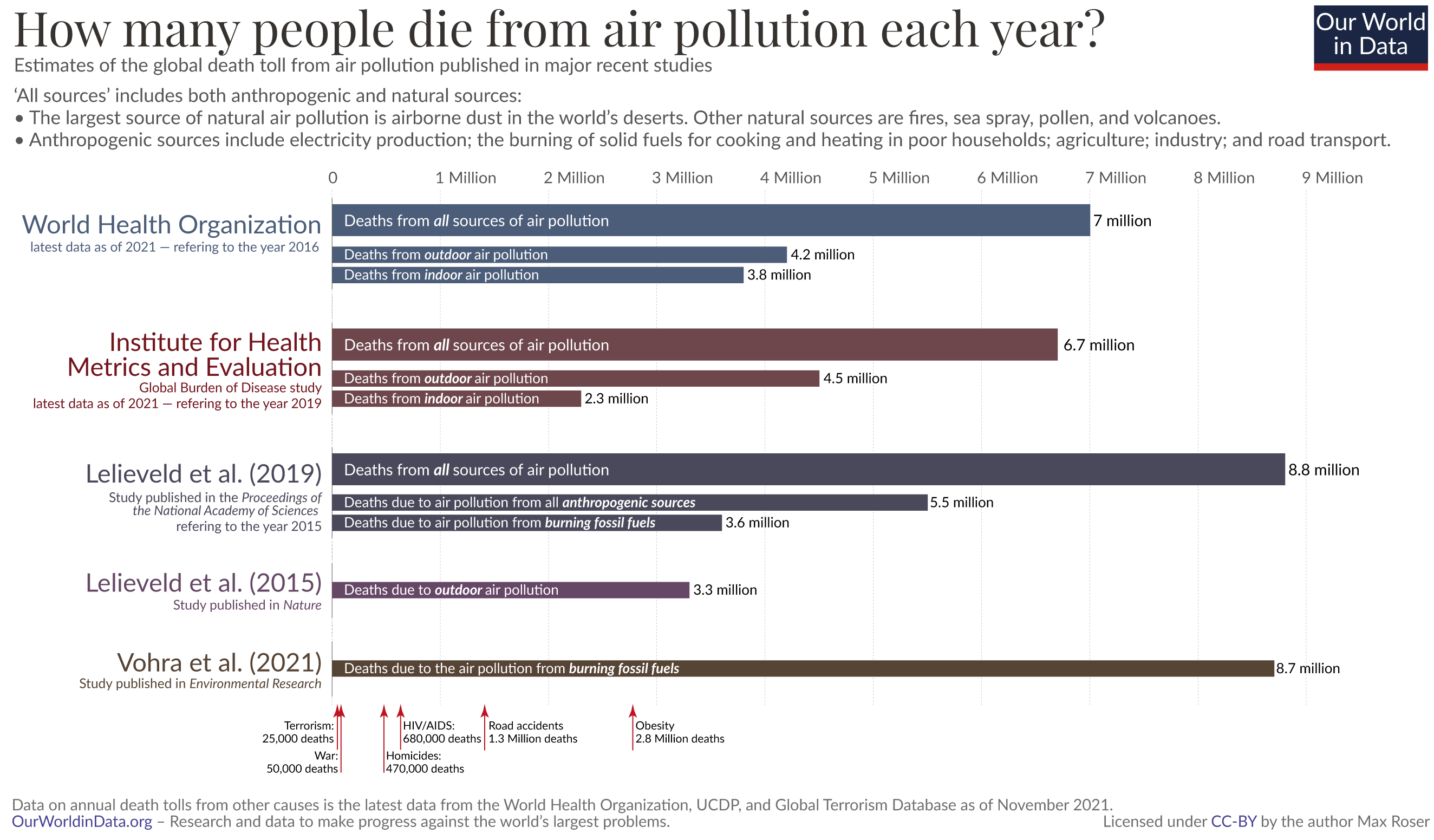

The purpose of this Data Review is to present the estimates of the global death toll from air pollution published in major recent studies and to provide the context that makes understandable what these estimates refer to.

The two most widely-cited estimates attribute around 7 million deaths per year to air pollution. But the published estimates span a wide range.

More recent studies tend to find a higher death toll than earlier studies. This is not because air pollution – at a global level – is worsening, but because the more recent scientific evidence suggests that the health impacts of exposure to pollution is larger than previously thought.

First I provide an overview and context to the problem of air pollution. This is followed by these estimates and explanations, given study-by-study.

Exposure to air pollutants increases our risk of developing a range of diseases. These diseases fall into three major categories: cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and cancers.

It makes sense to think of these estimates as ‘avoidable deaths’ – they are the number of deaths that would be avoided if air pollution was reduced to levels that would not increase the risk of developing these lethal diseases.

Death is, of course, not the only negative consequence of air pollution. Many millions more suffer from poor health as a result.

In this chart I plotted estimates of the death toll from air pollution.

The two most widely cited, and regularly updated estimates for the death toll from air pollution come from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the IHME’s Global Burden of Disease study. Their latest estimates are very close to each other – they estimate 7 million and 6.7 million deaths per year, respectively. These deaths are attributed to both indoor and outdoor pollution and – as explained below – stem from man-made and natural sources of air pollution.

In the last section of this text I discuss these studies and what each estimate refers to in more detail.

There are a number of pollutants that have negative health impacts. But there is one that all studies focus on: particulate matter.

Particulate matter – often abbreviated as PM – is everything in the air that is not a gas. These are very small particles made up of sulfate, nitrates, ammonia, sodium chloride, black carbon, mineral dust and water that are suspended in the air that we breathe.

Particles with a diameter of 10 micrometers (10 millionth of a metre) or less can enter deep inside a person’s lungs. But the most health-damaging particles are even smaller. Those with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less – abbreviated as PM2.5 – can penetrate the lung barrier and enter a person’s blood system. These are extremely fine particles: 2.5 micrometers is about one-thirtieth of the diameter of a human hair.1

All studies of the mortality impacts of air pollution consider our exposure to particulate matter. Some studies also consider the impact of ground-level ozone. The death toll from ozone is much lower than that of PM, but it is still considerable: it’s responsible for hundreds of thousands of premature deaths every year. Other air pollutants are rarely considered in global studies.

The published estimates of the death toll from air pollution span a wide range, as the chart above made clear. The number of deaths attributed to outdoor air pollution ranges from 3 million to almost 9 million per year. In addition, a large number of deaths are attributed to indoor air pollution.

The uncertainty intervals of the published estimates within these studies are large too.

This range makes clear that research on the global impact of air pollution is still in its early stage. More scientific research is needed to arrive at greater certainty. But it is also worth pointing out that all studies agree that the health impact of air pollution is very high; they agree that the annual death toll is in the millions.

Scientists today believe that the impact of a given level of pollution is larger than they previously thought

Researchers have known for a long time that air pollution leads to a large number of premature deaths. But, in the past, the relationship between exposure and health consequences was thought to be less strong. In more recent studies a given level of exposure is thought to lead to a larger number of deaths than in earlier research. The slope of the exposure-response-function is steeper than previously thought.

Very recent research suggests even steeper exposure-response-functions so that I would not be surprised if future global studies would attribute an even larger number of deaths to air pollution. As we will see in the study-by-study breakdown later, the exposure-response-function estimated by Heft-Neal et al. (2018) for Africa is steeper than the majority of global studies assume.2

Likewise, the study by Burnett et al. (2018) concludes that their “estimates are several-fold larger than previous calculations, suggesting that outdoor particulate air pollution is an even more important population health risk factor than previously thought.”3

Most major studies on outdoor air pollution – including the WHO and the IHME estimates – include the death toll from anthropogenic (man-made) and natural sources.

Anthropogenic sources of outdoor air pollution originate in a variety of human activities: the production of electricity (in particular in coal power plants); the burning of solid fuels (wood, charcoal, coal, crop waste and dung) for cooking and heating in billions of poor households; agriculture; industry; and road transport.

The largest source of natural air pollution is airborne dust in the world’s deserts. This form of particulate matter is a very large threat to the health of people in the arid regions of the world. A second major natural source is the smoke from wildfires in forests and grasslands. Additional natural sources are sea spray, pollen, and volcanoes.

It is possible to reduce natural air pollution to some degree. It is certainly possible to reduce exposure to it – better housing, less time outdoors during periods of high concentration, and filters in the household can all make a difference.

But anthropogenic sources of air pollution are of particular interest. We can massively reduce them by changing the technologies that we rely on. We can change the technologies that we rely on to produce electricity, to cook our meals, to heat our homes, to produce our food, and to power our transport.

The majority of studies considers both, natural and anthropogenic sources of air pollution. But there are exceptions: Lelieveld et al (2019) is a major recent study of indoor and outdoor air pollution that focuses on anthropogenic sources. According to this study 5.5 million people die prematurely every year due to anthropogenic air pollution. This includes the air pollution caused by agriculture, residential energy use, non-fossil industrial emissions, and fossil fuel burning.

These researchers study the impact of burning fossil fuels in particular. They find that the death toll from burning fossil fuels – in power generation, transportation and industry – 3.6 million premature deaths annually. This means that phasing out fossil fuels – and substituting them with clean sources of energy – would avoid an excess mortality of 3.6 million per year; this is more than 6-times the annual death toll of all murders, war deaths, and terrorist attacks combined (the death tolls are shown at the bottom of the chart above and sum up to about 545,000 deaths per year).

Reference:

For a big comparative overview of the impact of pollution on human health see: Landrigan PJ, et al. (2018) – The Lancet commission on pollution and health. In The Lancet.

Study-by-study: The global death toll from air pollution

WHO: 7 million premature deaths per year due to indoor and outdoor air pollution from anthropogenic and natural sources

The WHO estimates that:

- 4.2 million die prematurely every year from outdoor (ambient) air pollution.

- 3.8 million die from indoor air pollution.

- 7 million die in total from all sources of air pollution.

You will notice that the WHO estimates the total death toll to be lower than the sum of indoor and outdoor pollution deaths. This is because the deaths from risk factors are not summable. As the authors explain: “Some deaths may be attributed to more than one risk factor at the same time. For example, both smoking and ambient air pollution affect lung cancer. Some lung cancer deaths could have been averted by improving ambient air quality, or by reducing tobacco smoking.”4 Similarly the death of a particular person could have been averted by reducing the indoor or outdoor air pollution.

In this context it is important to know that indoor air pollution – caused by people living in energy poverty – is one of the largest contributors to outdoor air pollution. The pollution generated in their homes also creates pollution outside the home. This means that these same populations often suffer from both, high indoor and high outdoor air pollution.

As of November 2021 these are the latest WHO estimates of air pollution’s death toll. They refer to the year 2016.

References on the WHO’s air pollution estimates:

The WHO publishes two fact sheets that present the latest data:

- WHO (2021) – Fact sheet: Ambient (outdoor) air pollution

- WHO (2021) – Fact sheet: Household air pollution and health

The Global Burden of Disease study: 6.7 million premature deaths due to indoor and outdoor air pollution from anthropogenic and natural sources

The Global Burden of Disease study (GBD) estimates that in 2019:5

- 4.5 million people died prematurely from outdoor air pollution (from PM2.5 and ground-level ozone).

- 2.3 million died from indoor air pollution.

- 6.7 million died in total, from indoor and outdoor pollution.

As with most other studies, this study does not differentiate between anthropogenic and natural sources of air pollution. It includes both.

As of November 2021 these are the latest GBD estimates of air pollution’s death toll. They refer to mortality in 2019.

References on the IHME’s air pollution estimates:

- To see more details on these figures see the State of Global Air Report. This is the annual joint report by the Health Effects Institute and the IHME.

Lelieveld et al. (2019) in PNAS: 5.5 million premature deaths due indoor and outdoor air pollution from anthropogenic sources; 3.6 million deaths due to the burning of fossil fuels

The research by Lelieveld et al (2019) published in PNAS is a comprehensive recent study of indoor and outdoor air pollution.6

The following three death tolls are attributable to air pollution according to this study:

- 8.8 million deaths due to indoor and outdoor air pollution in total

- 5.5 million deaths from all anthropogenic sources

- 3.6 million deaths from burning fossil fuels

According to the authors 5.5 million people die prematurely every year due to air pollution from all anthropogenic sources. This includes the air pollution caused by agriculture, residential energy use, non-fossil industrial emissions, and fossil fuel burning. It is the sum of indoor air and outdoor air pollution that originates from anthropogenic sources.

Their study focuses on the impact of burning fossil fuels. They find that the death toll from burning fossil fuels – in power generation, transportation and industry – is responsible for 3.6 million deaths. This means that phasing out of fossil fuels – and a substitution with clean energy – would avoid an excess mortality of 3.6 million per year. The map shows the estimated death toll from fossil fuel air pollution.

Unfortunately the authors do not publish an estimate of the impact of indoor air pollution due to residential energy use alone.

The authors estimate that in total 8.8 million die prematurely due to air pollution every year. This most comprehensive measure of the death toll includes the air pollution from anthropogenic and natural sources of air pollution, such as desert dust.

For the total impact of air pollution (including natural sources) they estimate that the mean life expectancy decrease per affected person is about 26.5 years. As an average for the world population the mean loss of life expectancy is 2.9 years.

They consider two pollutants, particulate matter (including PM 2.5) and ground-level ozone.

The map below shows these estimates.

WHO: 4.2 million premature deaths per year due to outdoor air pollution from anthropogenic and natural sources

The WHO estimates that 4.2 million die prematurely every year as the result of exposure to outdoor (or ambient) air pollution. As of November 2021 this is the latest WHO estimates of air pollution’s death toll and it refers to the year 2016.

The 4.2 million deaths from outdoor air pollution are premature deaths “due to exposure to fine particulate matter of 2.5 microns or less in diameter (PM2.5)”. The WHO does not include the deaths caused by other air pollutants (such as ozone) and it should therefore be considered to be a somewhat conservative figure.7

The outdoor air pollution considered by the WHO stems from both natural (such as dust from deserts) and anthropogenic sources.8

References:

- The WHO’s main document is here: WHO (2021) – Fact sheet: Ambient (outdoor) air pollution

- A much more detailed, but not up-to-date study is: World Health Organization (WHO) (2016) – Ambient Air Pollution: A Global Assessment of Exposure and Burden of Disease (WHO, Geneva).

The Global Burden of Disease study: 4.5 million premature deaths due to outdoor air pollution from anthropogenic and natural sources

The results of the Global Burden of Disease study by the IHME can be found in their scientific publications (the scientific publication is usually published in The Lancet, the results can also be found on their website healthdata.org).

The specific results on the impact of air pollution can also be found in the annual report ‘State of Global Air’. This report is published jointly by the IHME and the Health Effects Institute.

According to this research 4.5 million people die prematurely every year due to outdoor air pollution.9 They consider the mortality impact of two pollutants, outdoor exposure to fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) and ground-level ozone.

The study does not differentiate between anthropogenic and natural sources of air pollution. It includes both.

As of November 2021 these are the latest GBD estimates of outdoor air pollution’s death toll. They refer to mortality in 2019.

References:

- To see more details on these figures see the State of Global Air Report. This report is published annually by the Health Effects Institute and the IHME.

- The latest major publication in the scientific literature is Cohen AJ, et al. (2017) – Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: An analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. In Lancet 389:1907–1918.

Lelieveld et al. (2015) in Nature: 3.3 million deaths due to outdoor air pollution

Lelieveld et al. (2015) focused on outdoor air pollution.10

Lelieveld et al. (2015) estimate that outdoor air pollution leads to 3.3 million million deaths per year. The 95 percent confidence interval ranges from 1.6 million to 4.8 million deaths.

The researchers consider exposure to particulate matter (PM2.5) and ground level ozone. Most deaths are caused by particulate matter.

This study includes both anthropogenic and natural causes of outdoor air pollution.

According to this research it is the outdoor air pollution caused by residential energy use – primarily heating and cooking – that has the largest impact on premature mortality globally. They estimate that one million outdoor air pollution deaths per year are caused by residential energy use and the authors note that deaths are “in addition to the 3.54 million deaths per year due to indoor air pollution from essentially the same source”.

Vohra et al. (2021) in Environmental Research: 8.7 million deaths due to the outdoor air pollution caused by burning fossil fuels

The study by Vohra et al. (2021) suggests that the death toll from outdoor air pollution caused by fossil fuels is much higher than other studies suggest. They estimate that 8.7 million deaths globally in 2018 were due to the air pollution caused by burning fossil fuels.11 8.7 million premature deaths are almost one-fifth of all deaths globally. The uncertainty intervals in this study are extremely high.

The authors only focus on particulate matter exposure; other pollutants (including ozone) are not considered.

Much of the paper focuses on estimates for the year 2012 for which the authors estimate a global death toll of 10.2 million premature deaths. The authors explain that the death toll has declined between 2012 and 2018; they attribute this to a decline in pollution in China.

The authors arrive at their very high estimate because they rely on a concentration-response function (CRF) that is different from the CRF in previous studies. This new CRF is taken from a recently published meta-analysis of long-term PM2.5 mortality association by Vodonos et al (2018).12

Heft-Neal et al. (2018) in Nature: Air pollution and infant mortality in Africa

This study does not focus on the global death toll from air pollution. It focuses on Africa and infant deaths. It is an important recent study that suggests that current estimates for the death toll of air pollution might be too low.

It constructs two datasets: one based on household surveys, which detail the time and place of nearly one million births across sub-Saharan Africa. Another dataset details the spatial distribution of exposure to PM2.5 based on satellite data.

The researchers estimate the impact of air pollution on mortality rates among infants in Africa. In many parts of Africa, exposure to PM2.5 is extremely high, both due to the reliance on solid fuels for cooking and dust from the African deserts (especially the Sahara).

They find that a 10μg/m³ increase in PM2.5 concentration is associated with a 9% rise in infant mortality. This suggests that PM2.5 exposure is responsible for 22% of infant deaths in the studied countries; this means 449,000 infant deaths in 2015 alone. This is an extremely high death toll that would suggest that the exposure-response relationship in these African countries is steeper than previous studies (including those by the WHO and IHME) suggest.

Reference: Heft-Neal, S., Burney, J., Bendavid, E. et al. (2018) – Robust relationship between air quality and infant mortality in Africa. Nature 559, 254–258.

Acknowledgement: I want to thank Hannah Ritchie for her feedback on this article.

Keep on reading on Our World in Data: